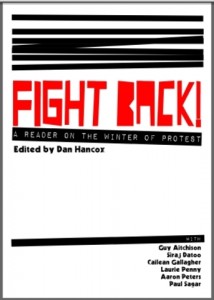

Die Wut und die Entschlossenheit der Studierendenproteste in Großbritannien in den letzten Monaten hat wohl entscheidend dazu beigetragen, den politische Raum für eine breite Bewegung gegen die Sparmaßnahmen der dortigen konservativ-liberalen Regierung zu öffnen. Bereits im Februar ist nun ein Reader online (ab Anfang April auch im Buchhandel erhältlich), der diesen heißen Herbst wie ich finde sehr eindrucksvoll nachzeichnet. Fight Back! A Reader on the Winter of Protest.

Die Wut und die Entschlossenheit der Studierendenproteste in Großbritannien in den letzten Monaten hat wohl entscheidend dazu beigetragen, den politische Raum für eine breite Bewegung gegen die Sparmaßnahmen der dortigen konservativ-liberalen Regierung zu öffnen. Bereits im Februar ist nun ein Reader online (ab Anfang April auch im Buchhandel erhältlich), der diesen heißen Herbst wie ich finde sehr eindrucksvoll nachzeichnet. Fight Back! A Reader on the Winter of Protest.

Fight Back! ist dabei vielleicht das erste Buch, das im Polizeikessel seinen Anfang nahm. Es enthält 350 Seiten Berichte, Analysen, Bilder und Reflexionen, die allesamt auf verschiedene Blogs verteilt veröffentlicht waren.

Am 10 November 2010 fand in London die erste Demonstration des heißen Herbstes statt, gegen neoliberale Hochschulpolitik und die Verdreifachung der Studiengebühren, mit 52.000 Leuten. Am Abend hielten etwa 200 Personen die Parteizentrale der konservativen Partei besetzt. Darauf folgte ein Monat mit Aktionen, Demonstrationen, Flashmobs und Besetzungen. Nina Power beschreibt den 10. November als eine „Sternstunde der Anarchie“:

Am 10 November 2010 fand in London die erste Demonstration des heißen Herbstes statt, gegen neoliberale Hochschulpolitik und die Verdreifachung der Studiengebühren, mit 52.000 Leuten. Am Abend hielten etwa 200 Personen die Parteizentrale der konservativen Partei besetzt. Darauf folgte ein Monat mit Aktionen, Demonstrationen, Flashmobs und Besetzungen. Nina Power beschreibt den 10. November als eine „Sternstunde der Anarchie“:

Die Demonstranten warfen Scheiben ein und arbeiteten sich aufs Dach vor. Aus Twitter-Nachrichten lässt sich schließen, dass einige ein Sofa aus dem Gebäude mit aufs Dach schleppten, mit dem ziemlich vernünftigen Argument „wenn wir schon eingekesselt werden, dann wollen wir es wenigsten bequem haben“. […] Die Gewalt ist schwerlich nur als mutwilliger Akt einer kleinen Minderheit zu sehen – sie ist authentischer Ausdruck der Enttäuschung über ein paar wenige, die entschlossen scheinen, die Zukunft für viele zu einem elenden, engstirnigen und Schulden beladenen Ort zu machen.

Als Leseprobe aus dem Reader hier ein Bericht über eben diesem Abend:

Inside the Millbank Tower riots

Laurie Penny, New Statesman

It’s a bright, cold November afternoon, and inside 30 Millbank, the headquarters of the Conservative Party, a line of riot police with shields and truncheons are facing down a groaning crowd of young people with sticks and smoke bombs.

Screams and the smash of trodden glass cram the foyer as the ceiling-high windows, entirely broken through, fill with some of the 52,000 angry students and schoolchildren who have marched through the heart of London today to voice their dissent to the government’s savage attack on public education and public services. Ministers are cowering on the third floor, and through the smoke and shouting a young man in a college hoodie crouches on top of the rubble that was once the front desk of the building, his red hair tumbling into his flushed, frightened face.

He meets my eyes, just for a second. The boy, clearly not a seasoned anarchist, has allowed rage and the crowd to carry him through the boundaries of what was once considered good behaviour, and found no one there to stop him. The grown-ups didn’t stop him. The police didn’t stop him. Even the walls didn’t stop him. His twisted expression is one I recognise in my own face, reflected in the screen as I type. It’s the terrified exhilaration of a generation that’s finally waking up to its own frantic power. Glass is being thrown; I fling myself behind a barrier and scramble on to a ledge for safety. A nonplussed school pupil from south London has had the same idea. He grins, gives me a hand up and offers me a cigarette of which he is at least two years too young to be in possession. I find that my teeth are chattering and not just from cold. „It’s scary, isn’t it?“ I ask. The boy shrugs. „Yeah,“ he says, „I suppose it is scary. But frankly…“ He lights up, cradling the contraband fag, „frankly, it’s not half as scary as what’s happening to our future.“

There are three things to note about this riot, the first of its kind in Britain for decades, that aren’t being covered by the press. The first is that not all of the young people who have come to London to protest are university students. Lots are school pupils, and many of the 15, 16 and 17-year-olds

present have been threatened with expulsion or withdrawal of their EMA benefits if they chose to protest today. They are here anyway, alongside teachers, young working people and unemployed graduates. What unites them? A chant strikes up: „We’re young! We’re poor! We won’t pay any more!“

The second is that this is not, as the right-wing news would have you believe, just a bunch of selfish college kids not wanting to pay their fees (many of the students here will not even be directly affected by the fee changes). This is about far more than university fees, far more even than the coming massacre of public education. This is about a political settlement that has broken its promises not once but repeatedly, and proven that it exists to represent the best interests of the business community, rather than to be accountable to the people. The students I speak to are not just angry about fees, although the Liberal Democrats‘ U-turn on that issue is manifestly an occasion of indignation: quite simply, they feel betrayed. They feel that their futures have been sold in order to pay for the financial failings of the rich, and they are correct in their suspicions. One tiny girl in anial-print leggings carries a sign that reads: „I’ve always wanted to be a bin man.“

The third and most salient point is that the violence kicking off around Tory HQ – and make no mistake, there is violence, most of it directed at government property – is not down to a „small group of anarchists ruining it for the rest.“ Not only are Her Majesty’s finest clearly giving as good as they’re getting, the vandalism is being committed largely by consensus – those at the front are being carried through by a groundswell of movement from the crowd.

Not all of those smashing through the foyer are in any way kitted out like your standard anarchist black-mask gang. These are kids making it up as they go along. A shy-looking girl in a nice tweed coat and bobble hat ducks out of the way of some flying glass, squeaks in fright, but sets her lips determinedly and walks forward, not back, towards the line of riot cops. I see her pull up the neck of her pink polo-neck to hide her face, aping those who have improvised bandanas. She gives the glass under her feet a tentative stomp, and then a firmer one. Crunch, it goes. Crunch.

As more riot vans roll up and the military police move in, let’s whisk back three hours and 300 metres up the road, to Parliament Square. The cold winter sun beats down on 52,000 young people pouring down Whitehall to the Commons. There are twice as many people here as anyone anticipated, and the barriers erected by the stewards can’t contain them all: the demonstration shivers between the thump of techno sound systems and the stamp of samba drums, is a living, panting beast, taking a full hour to slough past Big Ben in all its honking glory. A brass band plays the Liberty Bell while excited students yammer and dance and snap pictures on their phones. „It’s a party out here!“ one excited posh girl tells her mobile, tottering on Vivienne Westwood boots while a bunch of Manchester anarchists run past with a banner saying „Fuck Capitalism“. One can often take the temperature of a demonstration by the tone of the chanting. The cry that goes up most often at this protest is a thunderous, wordless roar, starting from the back of the crowd and reverberating up and down Whitehall. There are no words. It’s a shout of sorrow and celebration and solidarity and it slices through the chill winter air like a knife to the stomach of a trauma patient. Somehow, the pressure has been released and the rage of Europe’s young people is flowing free after a year, two years, ten years of poisonous capitulation.

They spent their childhoods working hard and doing what they were told with the promise that one day, far in the future, if they wished very hard and followed their star, their dreams might come true. They spent their young lives being polite and articulate whilst the government lied and lied and lied to them again. They are not prepared to be polite and articulate any more. They just want to scream until something changes. Perhaps that’s what it takes to be heard.

„Look, we all saw what happened at the big anti-war protest back in 2003,“ says Tom, a postgraduate student from London. „Bugger all, that’s what happened. Everyone turned up, listened to some speeches and then went home. It’s sad that it’s come to this, but…“ he gestures behind him to the bonfires burning in front of the shattered windows of Tory HQ. „What else can we do?“

We’re back at Millbank and bonfires are burning; a sign reading „Fund our Future!“ goes up in flames. Nobody quite expected this. Whatever we’d whispered among ourselves, we didn’t expect that so many of us would share the same strength of feeling, the same anger, enough to carry 2,000 young people over the border of legality. We didn’t expect it to be so easy, nor to meet so little resistance. We didn’t expect suddenly to feel ourselves so powerful, and now — now we don’t quite know what to do with it. I put my hands to my face and find it tight with tears. This is tragic, as well as exhilarating. Yells of „Tory Scum!“ and „No ifs, no buts, no education cuts!“ mingle with anguished cries of „Don’t throw shit!“ over the panicked rhythm of drums as the thousand kids crowded into the atrium try to persuade those who have made it to the roof not to chuck anything that might actually hurt the police. But somebody, there’s always one, has already thrown a fire extinguisher. A boy with a scraggly ginger beard rushes in front of the riot lines. He hollers, „Stop throwing stuff, you twats! You’re making us look bad!“ A girl stumbles out of the building with a streaming head wound; it’s about to turn ugly. „I just wanted to get in and they were pushing from the back,“ she says. „A policeman just lifted up his baton and smacked me.“

Originally published in the New Statesman, 11 November 2010

[…] Hochschulpolitik sehr gut zusammen. In diesem Zusammenhang sei auch erneut auf den Reader “Fight back” verwiesen, der ebenfalls die Kämpfe gegen die Studiengebühren zum Thema […]